by Cory Rieken

In the mid-1990s, I supported diversity training for a large tech firm. I managed the outside suppliers and became certified to facilitate diversity programs. Now that I work for a training supplier, I’ve been struck by a growing wave of customer requests for diversity and inclusion training, and I have an intense desire to avoid the mistakes of the past. This topic is dear to my heart, and I’d really like us to get it right this time.

Diversity was a huge initiative for corporations late in the last millennium. Many current corporate leaders went through diversity training long ago in their careers, yet today we face a barrage of data and media stories exposing the severe lack of progress in this area.

What went wrong back then? Are we doomed to mediocre, if any, results from our current initiatives?

Not if we approach today’s programs with a new definition and a new mindset.

Gaining a new mindset requires us to examine the old and how it’s hindered our progress. Here’s a personal example, which didn’t occur to me until recently, 34 years after it happened: When I started working at that large tech firm, we had a fantastic employee activity center with lots of sports leagues and clubs. I was in the finance area of a large corporate services department, and as is typical of some work groups, we often socialized. The sports teams offered a way to organize this.

The guys in the department formed a basketball team. The leader of the department was included. Now, at five feet, three inches tall, and not being male or good at basketball, I wasn’t invited to play. Makes sense—it was a men’s league, after all. But I was quite literally invited to the sidelines to cheer on the team. And I went. It was fun.

The guys practiced together, sometimes went to lunch together, and sometimes invited me and the other women "cheerleaders" to lunch, and sometimes they didn’t. We became a social group, but the men met together more often as they practiced and played.

As they bonded, interesting things began happening at work. When new technology projects came up, they were typically assigned to one of the men on the team. I would volunteer and be offered a chance to work on the new projects, but I wasn’t usually approached to lead them. When it came time to support the local marathon as a department project, I was asked to head that.

Hmmmm... a major project that impacted crucial systems and processes was not something I could lead, but finding enough cups, bananas, and tables for an event was. And this was all fine with me at the time. I was complicit in my own sidelining. Content to be a cheerleader forever, and not a key player.

Back to diversity training. In the nineties we focused on awareness. We tried to change people’s mindsets by showing the different advantages and opportunities some people had simply because of their race or gender. We tried to make everyone conscious. As you can imagine, this type of training wasn’t wildly embraced by everyone, especially the people who felt accused of being "advantaged."

A book excerpt printed in Time on February 5, 2018 titled, "How Diversity Training Infuriates Men and Fails Women," sums up the experience perfectly. The author, Joanne Lipman, refers to the same type of training that we had at my company—the training I oversaw. I was complicit in the infuriation of men. Heck, I was complicit in the infuriation of everyone. We all went away feeling that others judged us unfairly.

We formed empowerment groups that could seem exclusive. Although anyone could attend meetings, did we really think a lot of men were going to be in the women’s initiative? One of my colleagues joked that he was going to form "the tall guy’s initiative" when he bumped his head on one of the TVs hanging in a training room.

We can’t make the same mistakes again

There is a big risk of repeating our errors right now because of the focus on "unconscious bias." Don’t get me wrong, we need to address this. Yet often it seems this is a different term for the same thing we tried to surface in the nineties by highlighting the advantages some people had by virtue of birth.

Yes, unconscious bias exists. But we don’t know we have it. It’s named "unconscious" for a reason! And it’s very, very human. Think about survivor or winner bias: we like to be associated with success. It’s natural. When my favorite college football team is victorious, I shout "We won!" When they lose...well, you get the picture. I didn’t have anything to do with the win or loss, but I’ll claim one and not the other. I bet you do, too.

Bias is a value-based thing. It resides in our view of different types of people, conscious or not. Corporations can promote and reward certain values, but changing a person’s inner values with training is difficult, especially if the person isn’t aware of them. Using only training to make someone conscious of a factor they don’t know affects their decisions didn’t work a generation ago and it’s not going to work now.

You can’t put leaders in the fishbowl of a classroom and expect them to admit to unconsciously holding other people back. Seriously, who’s going to do that? And if you run pilots of this training with your senior leaders in the back of the room "evaluating" how good the training is, what participant in their right mind is going to have an epiphany and risk their career? "Yes, I’ve been promoting the people I like, not the people who deserve it! Thank you for making me conscious!" said no one ever.

Absolutely, we need to address the existence of unconscious bias, and we must be careful not to attempt forced therapy during training, or we will end up with resentment, backlash, and no change for another 20 years. It’s one thing to have class participants examine the different types of bias that exist, it’s quite another to expect them to eliminate all bias with new awareness.

There will be some "a-ha" moments. Let’s build on those moments with interaction skill-building and leadership coaching. Let’s institutionalize diversity and inclusion using bias-free recruiting and selection, performance management, high-potential identification, and succession planning. Unless we examine and improve our talent processes, today’s awareness training will leave us in the same situation we had in the nineties. At its heart, diversity and inclusion is about surfacing and accelerating potential. Everyone’s potential. That means purposefully giving people opportunities to succeed.

Classroom training has changed over the past two decades, as well

We no longer sit still for one topic over two days. Customers have been pushing learning providers for shorter and more impactful training for decades. That means we all attempt to change behaviors in four hours or less. Study after study has shown behavior change results from learning that happens over time. Multiple touches, such as assessment before classroom training and reinforcement activities afterward, plus ongoing coaching and practice, are what make behavior change sticky. Don’t fall into the four-hour awareness training trap.

One other thing we must get right this time: We must help people examine their own part in their circumstances. This means building the skills necessary to become a valuable, high-potential employee.

What would have happened decades ago if I had examined my own confidence level when I was okay with being sidelined? How much stronger could my performance have been if I’d powered up my own network or strengthened my leadership brand? What if I had risked failing more often instead of avoiding risk to appear competent? Today, I’m aware of my own complicity. I step up to leadership informally, every chance I get. I include people I don’t automatically agree with on projects. I strive to be open to feedback and I’m looking beyond myself for answers.

It’s time for a new way of thinking

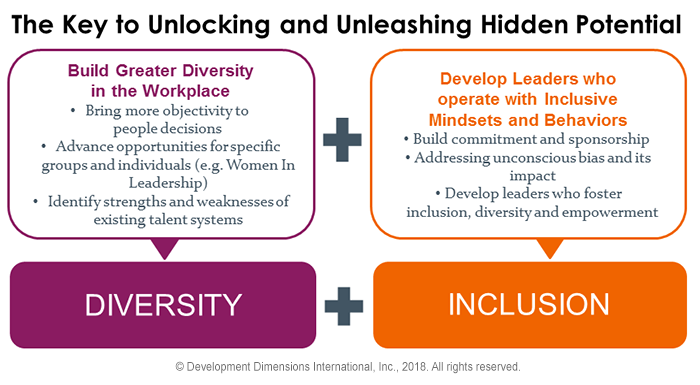

The graphic below shows the new mindset:

In my next blog, I’ll further explain why training is only part of the solution, and what else organizations need to do get diversity and inclusion right.

Download the new DDI eBook, Unleash Hidden Potential: Build Your Competitive Edge Through Diversity And Inclusion.

Cory Rieken is an executive advisor, Leadership Insight and Growth, for DDI, dedicated to improving leadership with and for her clients in creative and measurable ways. When not focused on clients, Cory is focused on family and is a curious learner about all things facing "The Sandwich Generation."

Topics covered in this blog