by Jim Thomas, Ph.D.

We’ve been hearing about the nursing shortage for years. And rightly so.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that almost two million nursing vacancies will be created over the next seven years. At the same time, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing notes that enrollment in nursing schools will fall far short of demand.

But there’s another nursing shortage that, although less frequently discussed, promises to derail efforts to achieve healthcare providers “triple aim” goals. It’s the looming nursing leadership shortage.

The growth in the nursing population necessitates an accompanying growth in the number of leaders who supervise and manage those entering the field. But that’s only part of the problem. Many organizations I work with are having trouble filling their existing nurse leader roles.

Let’s look at why this is so.

Understanding the Nurse Leader Shortage

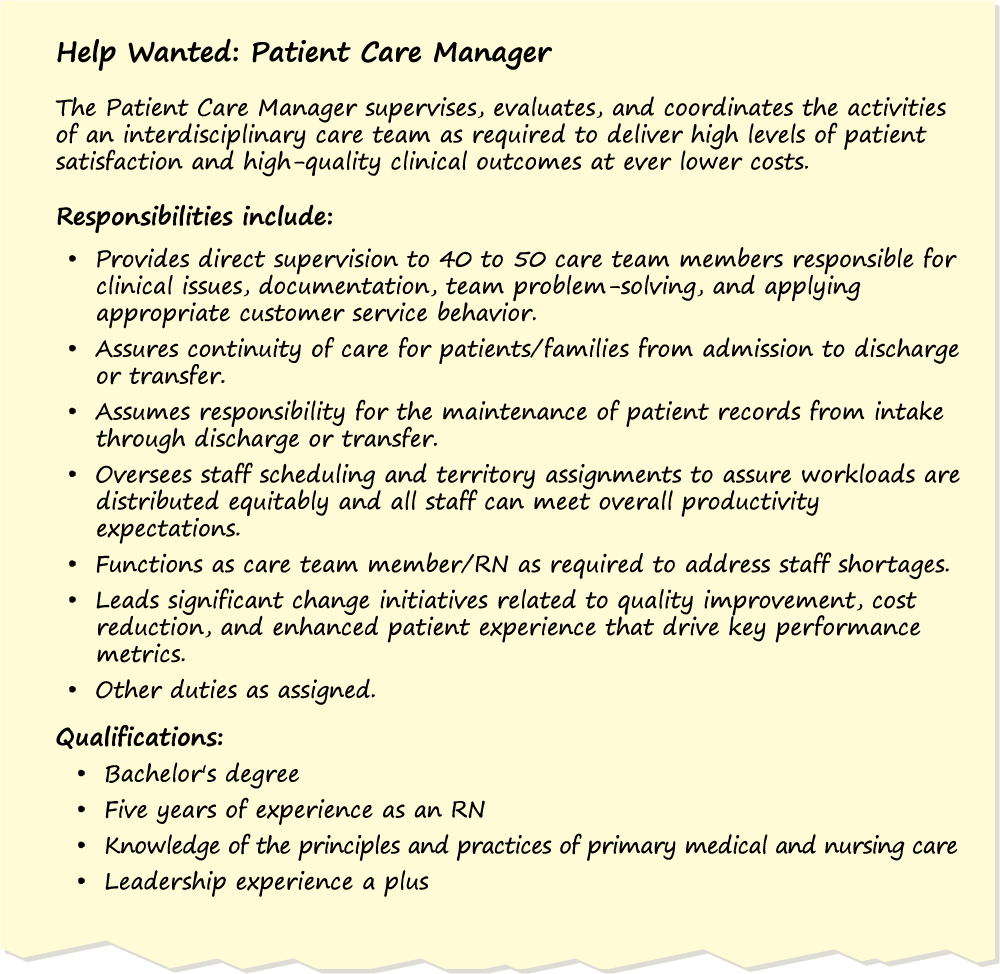

To understand why the current shortage exists, consider a typical job description for a patient care manager, like the one shown in the graphic below.

This job description provides valuable clues as to the root cause of the constricted leadership pipeline.

The typical nursing leader has 40 or more direct reports along with responsibility for driving quality outcomes and improving operating efficiency.

As if this wasn’t tough enough, many of these leaders enter the job with precious little leadership training and experience.

These jobs place rookie leaders into a role defined by a huge span of control, tremendous responsibility, and the need to step back into a non-leadership role whenever staffing shortages crop up (and they frequently do).

It should come as no surprise, then, that many organizations are having a hard time convincing nurses to become leaders.

Those organizations that try offering financial incentives are likely to be disappointed. Given the long hours a typical patient care manager puts in, these new leaders often find their compensation, when calculated on an hourly basis, is less than many of the experienced nurses they supervise! And that’s after accounting for bonuses or other perks.

One approach forward-thinking HR leaders are investigating is to redesign the patient care manager job so that it’s a more attractive, less demanding role. These efforts are grounded in the recognition that it’s unreasonable to expect a frontline leader to adequately address the needs of 40 to 50 direct reports. (In my experience, spans of control for frontline leaders in most other industries typically max out at 10 to 15 direct reports.) But these well-intentioned efforts to redefine the patient care manager job and reduce spans of control run smack into financial realities (“We can’t afford to create more leader levels/jobs!”) as well as the existing shortage of leader candidates (i.e., creating more vacancies that can’t be filled isn’t a solution).

It’s clear that the demands on healthcare leadership talent aren’t going to diminish any time soon. If anything, they will increase dramatically. Driving initiatives to enhance patient safety, improve the quality of clinical outcomes, and elevate levels of patient satisfaction would be tough enough in a stable and well-funded organizational environment.

But that’s not the world of modern healthcare! And it’s only going to get more complex and demanding for leaders.

The Solution Isn’t More Leaders

The solution isn’t to find more leaders—that’s simply not realistic given the demographic and operational realities facing healthcare organizations. The answer, instead, lies with expanding the capacity for leadership across the entire employee population. In short, we don’t need more leaders, we need more leadership!

There’s no shortage of talent within the nursing, allied health, and support services professional ranks. In many cases, the best and brightest young people enter these fields with exceptional academic credentials and receive the finest technical training available anywhere in the world. But their training often focuses exclusively on clinical and professional skills, with little emphasis placed on developing their latent leadership capability. It’s no surprise, then, that many organizations find they have a constricted pipeline for their leadership roles.

Unfortunately, the common organizational efforts when it comes to leadership potential are making things worse instead of better.

Instead of cultivating leadership capability across a broad swath of the workforce, many organizations are taking the opposite approach. A recent global survey DDI conducted found that approximately 75 percent of organizations have a program to identify and develop “high potentials” for leadership roles. These programs typical target only the 10 to 15 percent of the workforce deemed “emerging leaders.” The thinking is that a few “heroes” will be sufficient to satisfy the organization’s leadership requirements.

Well-conceived and properly executed “hi po” initiatives do need to be part of the solution (though research calls into question the typical program’s effectiveness, as explained in a popular DDI eBook), but these programs will fall far short of addressing the huge leadership gap looming in healthcare.

There are four things an organization can do to create more leadership capacity:

1. Define the leadership behaviors critical to your organization’s success over the next three to five years.

Whether this definition takes the form of a competency model, a leadership playbook, or a set of critical behaviors, the key is to clearly capture what you expect of your leaders. This definition is a necessity for selecting, developing, coaching, and rewarding leadership behavior. Many organizations fail to create a culture that develops leadership at all levels simply because they don’t define what they mean by “leadership” in sufficient detail.

2. Align existing leaders around what it means to have leadership potential.

Being a high-performing individual contributor or a technical expert can easily be confused with having the ability to grow and develop into a leader. It’s not the same thing!

Organizations that cultivate leadership at all levels know what to look for and are constantly seeking out latent leadership potential. Once they spot it, they can then provide leadership growth opportunities and coaching, and reinforce and reward the right behaviors.

The truth is that leadership potential is a tricky concept and those individual contributors who possess true leadership potential aren’t always easy to spot. Individual contributors with high potential for leadership may be less outgoing, but more thoughtful and introspective—two attributes that can predict future leadership success!

Others with leadership potential, meanwhile, may simply lack confidence. For example, analysis of thousands of behavioral assessments of leaders conducted over the past 20 years by DDI shows that women and men demonstrate similar levels of leadership skill. But while men may be overconfident when it comes to their leadership capabilities women are more likely to underestimate theirs. (This may help explain why men, even though they hold a minority of all healthcare jobs, are over-represented in healthcare leadership roles.)

Another challenge related to defining leadership potential is the “like me” bias. Without a clear set of criteria to define leadership potential, the natural human tendency among senior leaders is to create budding leaders in their own image. We need look no further than the dismal diversity statistics for most organizations to find proof of this evaluation error.

3. Relentlessly scout for talent and unleash this potential.

My work with healthcare professionals over the past 30 years reinforces my basic belief that there exists a wealth of talent within the industry, but this latent leadership potential is going largely untapped.

One solution is to leverage scalable and objective assessment tools that can measure leadership potential. Well-researched and validated tools are available to healthcare organizations, but few use them. Keep in mind, though, that these tools should not be confused with the plethora of feel-good personality-based tools that provide “self-insight.” These have their place, but they weren’t designed to be and shouldn’t be used as a substitute for instruments that have been built and validated in accordance with accepted professional standards for psychological assessments.

Failure to accurately assess leadership potential only partially explains why the reservoir of talent within most organizations remains underutilized, however. Even when potential is identified, current leaders frequently do a poor job of identifying and making meaningful job assignments available to emerging leaders in order to grow their skills and build their confidence.

What’s more, when managers have poor delegation and coaching skills, they can decrease confidence and transform emerging leaders into “anti-leaders.” Imagine looking upward in your organization and seeing a stressed out, over-burdened leader who refuses to share responsibility. It’s what many nurses see. Is it any wonder that many of the most talented ones, a critical mass of whom have significant leadership potential, don’t aspire to leadership roles?

Training to enhance the coaching and delegation skills of current leaders is a good first step. But organizations also need to be more creative about how they engage nurses in improvement projects, organizational change initiatives, and other opportunities allowing them to exhibit leadership skills. This may require incentivizing both leaders and individual contributors, but the potential payoff in terms of leadership capacity is well worth the investment.

4. Make leadership development more broadly available.

In many healthcare organizations, it’s difficult enough to provide meaningful leadership development to existing leaders, let alone to those in non-leadership roles who have been identified as having leadership potential. Layering leadership training on top of training to maintain and/or enhance clinical skills, and mandatory training to meet regulatory requirements just adds to the challenge.

Clearly, traditional approaches to leadership development that rely primarily on classroom training aren’t practical in today’s environment. While research shows leaders still value this mode of leadership instruction, reaching a broader audience of emerging leaders requires more scalable options, including:

- Web-based learning

- Peer learning

- Self-paced learning via completion of on-the-job activities

- Peer learning and social networking

- Mentoring and coaching

Successful efforts to develop the untapped well of leadership talent will undoubtedly need to encompass multiple learning modalities. The key to success will be engaging learners to own their learning and to reinforce development efforts and progress.

The Only Way Forward

The unavoidable reality is that healthcare organizations face a massive leadership talent gap. And brilliant acquisition strategies and ambitious investment programs will not deliver on the triple aim goals providers are so passionately pursuing if they fail to address the leadership gap at the frontline.

This gap won’t be filled by identifying a small number of heroes or by opening up more primary care manager jobs. It will only be filled if organizations energize and activate the leadership potential of the entire workforce.

Learn more about DDI’s healthcare practice and our solutions across the continuum of care.

Learn more about how to unleash potential in your organization and download the new eBook, The Revolutionary Guide to Rethinking Leadership Potential.

Jim Thomas, Ph.D., is a DDI vice president who’s held a variety of roles spanning consulting, business development, and general management in his 23+ years with the organization. His work has literally taken him around the world, including extended expat assignments to the Middle East and China.

Aside from his passion for helping organizations acquire and engage talent, Jim’s personal interests mirror his active, globe-trotting DDI career. He’s a private pilot, an accomplished sailor, and an avid motorcyclist. That blur that just whizzed by? Yeah, that was Jim.

Topics covered in this blog