by Cory Rieken

In my last post, I reflected on what has gone wrong in the past with diversity training and suggested we needed more than just awareness. Let’s see what else we need to get right, and as with any business initiative, let’s keep the end in mind: better business results.

The Business Case for More Than Training

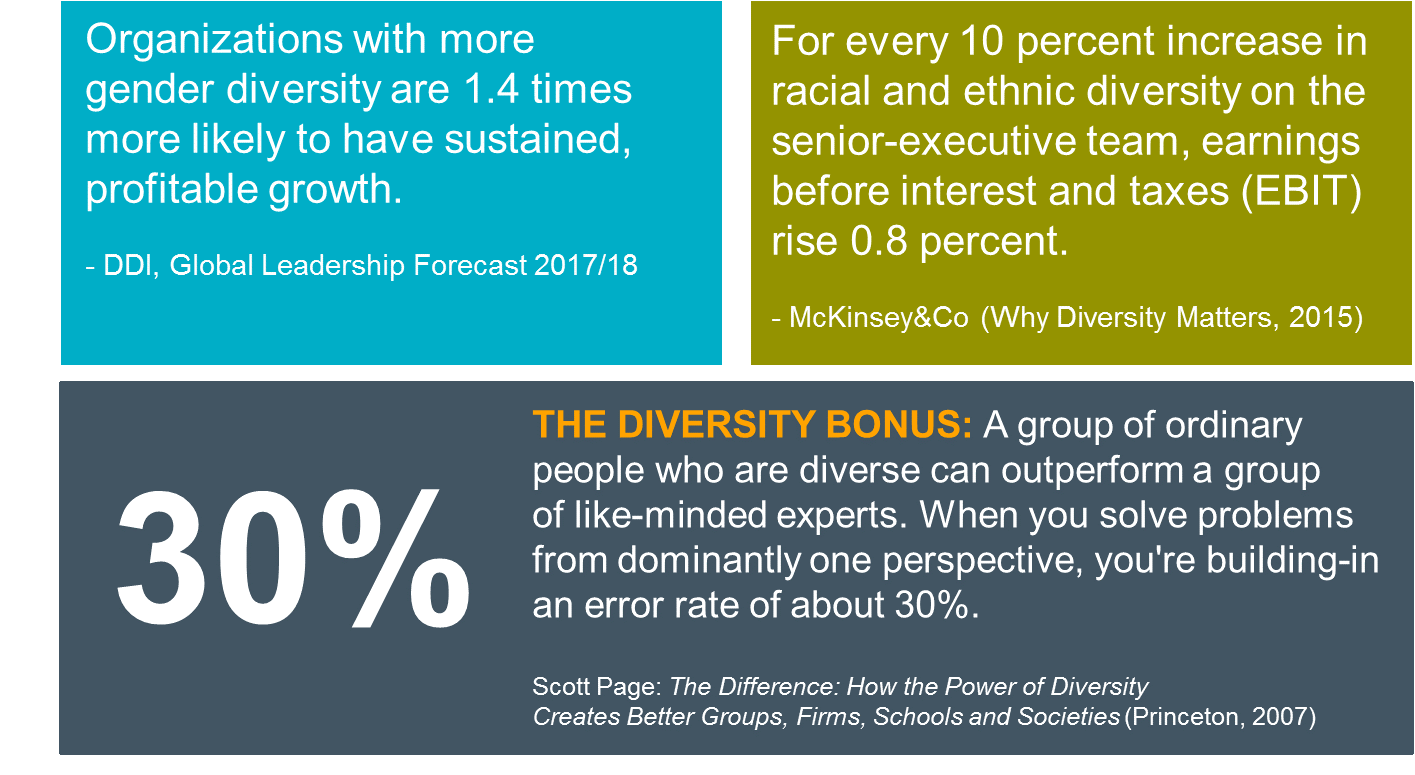

Plenty of studies demonstrate that diversity isn’t just a “right thing to do” exercise:

Notice that none of those results are about awareness training. This is a business case your senior operations or business leaders can relate to and champion. Enlist them as your messengers often. Maybe they are already kicking-off your awareness training and could use stats like these to showcase the benefits brought on by diversity.

You can also create an ongoing communication plan highlighting all the other great things your company is doing that will help everyone reach their highest potential, and make the communications come from those champions. Don’t make it about diversity – make it about the outcomes that diversity brings. Active and visible high-level sponsorship helps your employees take the awareness training seriously, because getting these results requires willingness from all leaders to change how they work.

Beyond communication, you probably have some big pressures impeding progress in diversity and inclusion:

This picture shows how strong the cultural push is. Your culture is made up of your company’s espoused values – what you say you believe – and your leaders’ and employees’ actual behaviors. It’s kept in place by your processes, policies, systems, and procedures, whether they are officially written or not.

Increasing diversity and including more people is a massive cultural effort. When you try to tackle this through awareness training only, the effort isn’t usually enough to push the lever down and drive diversity upward. You risk leaving untouched the very parts of your culture which keep the status quo in place. Better impact comes when you change how you select, develop, manage performance, and plan succession to ensure inclusion happens as part of all your talent processes. Let’s go through these in more detail:

Hiring and Promotion

First, you must define the criteria for success in each role, because you can’t hire “great” if you haven’t defined “great.” I cannot speak more eloquently about this than my colleague Katy Campbell did in her blog, “What Can Greg Brady Teach Us About Mislabeling Talent?” Then you have to select based on that criteria, and even here old thinking can block diversity and inclusion. Let me take you back to my former organization, where we did do some things right.

That big tech firm I worked for found new ways to invite more people into the hiring process. While we had great success hiring capable technical folks from certain programs at certain universities, we had to look hard at why we were only going to those schools. And it boiled down to credentials, not competencies, so we expanded our college recruiting program to new schools, with an eye toward diversity.

We knew what good looked like in terms of skills and competencies, so we challenged our own thinking on where we would find it. And it worked. We also supported what would now be known as STEM programs at the high school level to inspire young people to move into science and engineering. We had active Junior Achievement programs and sponsored robotics and other science contests at the middle school level. This long-term thinking was intended to create excitement about our company, name recognition, and grow the pool of competent future candidates.

Finally, make sure you have diverse people involved in the interview process and train them in behavioral interviewing, decision criteria, and all the legal aspects of interviewing. In short, successful companies honestly examine how their recruiting policies, processes, and systems are driving or hindering diversity and inclusion. If the processes are in the way, they change them.

Training & Development

Now I want to introduce a hypothetical organization that may sound like one you know. I swear, I have no particular organization or people in mind with this example – no live organizations were harmed in the making of this blog. (Admittedly, this might be a composite of several organizations I’ve worked in or with over the years.)

Company X has a “high sense-of-urgency” culture. They pride themselves on getting things done quickly. Agility is one of their favorite words. Getting things done well is important, too, but the organization has been known to do things fast, but they often have to do them over again. Quality and productivity metrics are trending downward – maybe not dramatically, but enough. HR has the task of getting every leader through unconscious bias training in the next six months. But no one thinks diversity training will fix the do-over problem, and they are probably right.

Company X's leaders have to do more, do it faster, and do it with less. They often delegate projects or tasks to accomplish more and accomplish it faster. Most of the leaders delegate to their “go-to guys” – the people they trust to do the job. These “go-to-guys” are dependable, and always there to take on more. Sounds great, right?

I challenge you: think about this with a long-term view. In our Global Leadership Forecast, only 14 percent of over 2,500 organizations say they have good leader bench strength. Fewer than one-sixth of reporting companies think they have the leaders they need for the future. That is a frightening statistic.

If our fictional organization keeps using their “go-to-guys” to get things done, are they overlooking other people who could have been given development opportunities? Could they be using delegation differently? Where does taking the path of least resistance leave them in terms of true capability, agility, and future leadership? And worse, but still not uncommon…what if the term “guys” is literal, as it was in the previous example I gave in my last post about the basketball team members becoming the “go-to-guys”?

Delegation for development requires leaders to scan their teams for people who need to learn. It means being willing and able to coach, monitor, provide feedback, and connect their delegate to others who will support their success. It’s purposeful; it takes time and energy. It’s also one of the most powerful developmental tools your organization currently has for building bench strength. So, you don’t need just D&I training, you may need delegation training, too. You may need to help leaders learn how to coach different people for developmental purposes – a different kind of training and skill-building. Why not use your coaching, delegation, and other leadership training to challenge people to think beyond the “go-to-guys”? Weave inclusion into all your training.

Succession & High Potential Development

No surprise, Company X’s high-potential (“hi-po”) pool is full of the “go-to-guys.” There are 40, because that’s what fits into a large classroom and they heard it was about the right number. These folks will save the future, right? After all, Company X says, “we have evidence these people can get things done! Isn’t that data enough?” No. By only counting on a few, they are ignoring the potential of the many, and they aren’t thinking about the challenges of leadership transitions. They only know these people are good at what they’ve done in the past.

High-potential identification and succession planning must be part of your diversity and inclusion efforts. Your culture, even a well-intentioned and positive part of culture, such as “high sense of urgency,” can work against those efforts. To find high-potentials and move them toward readiness, you first have to answer, “readiness for what?” and “potential to do what?” Defining what great looks like and then scanning a broader group of employees against those criteria, not against each other, will help you avoid creating a hi-po pool based only on performance in a current role. Far too many 9-box efforts have performance on one axis and “I like that person” on the other.

Ok, I know – it’s not labeled that way, of course, but perhaps you’ve watched a leader fighting hard to have someone included in a hi-po cohort but they just can’t articulate why. It’s because they like that person.

Here’s a challenge: ask every leader you meet today to define potential for you. See if you get any commonality. Without calibrating the leaders who identify potential around a common definition of the word potential, you risk expecting too much of people who are great in their current role without gathering any data about whether they are suited for higher leadership.

The best and easiest way to gather data is through consistent assessments that measure people apples-to-apples on the same competencies and behaviors. Assessments can help eliminate familiarity bias, which is often unconscious. Familiarity bias is the tendency to associate with or give work to the people with whom we are most familiar. The best assessments of potential combine behavioral components with data about personal attributes. Personality alone is not enough.

For example, aren’t demonstrated behaviors more important than a preference for introversion or extroversion? One of the best public speakers I have ever met is also one of the most introverted people I know. She is great at what she does, and she loves it enough to continue even though it saps her energy and she needs a lot of quiet time afterward to recharge. Most of us have some hindering aspect of our personality that we have learned to overcome or manage while at work. This is why you need to look at competencies – what people can do – as well as personality.

Finally, if you aren’t looking at the broader population for great leadership, you are robbing your future organization of potential business success. Maybe you don’t need 200 more leaders soon, but you probably want most people exhibiting leadership qualities. By scanning for potential more broadly against a common set of criteria, you’ll build in diversity and find a wealth of talent that you may be overlooking now.

Performance Management

Our hypothetical organization formally reviews performance twice per year, and they hope leaders are having ongoing performance discussions with their people all year long. Because the forms are officially due twice, most leaders are having a short conversation mid-year and a lengthy formal conversation at year-end. (They have lots of real work to get done quickly, remember?) Performance ratings are assigned, and the “go-to-guys” are consistently ranked high.

The organization made sure the “go-to-guys” had lots of chances to excel by delegating the most projects to them, even when that meant unintentionally preventing other people from shining. So, the “go-to-guys” also ended up having more conversations with their leaders throughout the year, because they were working on high-visibility projects. But this resulted in the leaders having less time to spend with other team members. Are you seeing this vicious cycle of exclusion?

You can avoid this trap by making inclusion a part of your performance process. Challenge your leaders to spread the wealth – make it part of their performance goals to delegate more to different people. Give your leaders the skills and easy tools to have more frequent performance conversations with everyone. And make inclusion part of the leadership performance criteria.

When communicating about performance management, do you take the opportunity to remind leaders of their unconscious bias training and how bias affects performance ratings and conversations? If you don’t, you are reinforcing the idea that unconscious bias training was not really important to everyday work.

In performance management, as in all talent processes, a clear definition of what good looks like in a role is critical. Success Profiles give talent reviewers a clear set of criteria to review people against, which helps get unconscious bias out of the way. When leaders review people against a clear set of knowledge, experience, skills, and personal attributes, they are far less likely to give biased feedback, and more likely to be objective about development needs.

By weaving diversity and inclusion through all your talent processes, you have much greater ability to impact the parts of your culture that are negatively affecting your efforts. And you’ll have examples to give during diversity training when someone asks, “What is our company doing besides putting people through this class?” (You know you’ve heard that question before.)

Download the new DDI eBook, Unleash Hidden Potential: Build Your Competitive Edge Through Diversity And Inclusion.

Cory Rieken is an executive advisor, Leadership Insight and Growth, for DDI, dedicated to improving leadership with and for her clients in creative and measurable ways. When not focused on clients, Cory is focused on family and is a curious learner about all things facing "The Sandwich Generation."

Topics covered in this blog